Here are the details for our current exhibition at the Glamorgan Archives

General Update

November 17th, 2018 by Admin 1 comment »So sorry for lack of posts this year, no reflection to a lack of activity or exhibitions.

Since our wonderful city showcase at the Cardiff Story Museum we have had a number of exhibitions:

June 2018

University Hospital of Wales

July 2018

Haydn Ellis building, Cardiff University

St Fagans

November 2018

Amanda Cashmore from the BBC interviewed Dr Ian Beech regarding the role of Whitchurch during WW1 and especially its treatment of shell shock, see link below

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-45892116

Remembrance Event at the National Museum

Whitchurch Village Library as part of Remembrance Sunday

Rhydypennau Library – small WW1 display until the end of the week

New Exhibition at the Cardiff Story Museum

February 23rd, 2018 by Admin 1 comment »We are very pleased to announce our next exhibition from Saturday the 3rd of March at the Cardiff Story Museum based in the old library building on the Hayes in the City Center.

We will have the City Showcase space which is downstairs and the exhibition will share some of the stories of those who worked and were treated at Whitchurch Hospital. There will also be some artefacts on display from Whitchurch.

The exhibition will run from Saturday the 3rd of March until Sunday the 3rd of June 2018

Photo taken by Eyes2Me Photography

New Exhibition – Whitchurch Hospital – Moving On

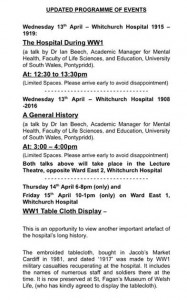

February 22nd, 2017 by Admin No comments »We are very happy to announce our next exhibition at Cardiff Central Library opening on the 6th of March

Please come along and have a look at the exhibition and have a look at the events on during the week

The events are listed on Eventbrite:

Guest blog post from Tim Bennett, Quality Improvement/Governance Nurse with Mental Health Services for Older People (MHSOP)

December 2nd, 2016 by Admin No comments »The Summer House

What is the summer house? I can tell you what it means to me – it’s not just one thing!

It’s a school, a fear, a resting point, a home and playground too. A community, a smoking shelter and a sanctuary for who?

The summer house outside Ward West 1A, photo taken by Tim.

A School – I remember – warm sunny days, green trees, excitement at my new job and getting a qualification at the end of it. Some of my learning on placement took place in the summer house. Debates and discussion with different members of the clinical team, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, OTs and social workers. Books, pens and note pads – patients as case studies, illness and diagnosis, treatments with talking, with medication with ECT, psychiatry, psychology – a bewildering array of topics and subjects. What a place to learn! This was my classroom for a brief period of time.

A Fear – someone is missing from the ward or failed to return from leave – a search needs to be undertaken. If there was any suicide risk we were told to look up into the trees, just in case. Check the summer house – under the benches, around each corner, look up, and check on top also. Fortunately for me and gladly for the patients that were missing – I never did find anyone who had committed suicide. It remained a fear of mine until we left Whitchurch, the thoughts remain with me even now that I no longer work there.

A resting point – for the years I worked in Tegfan day hospital, in the grounds of Whitchurch, one of the summer houses provided a midpoint between both buildings. On our zigzag journeys, around the site, this was frequently a resting point for those with physical disabilities to stop and rest – for others it was a point to sit and have a cigarette. This was always a social occasion of those gathered – one thing in common, the hospital. Patient, staff or visitor, there was a draw to sit and stop. Was this truly asylum – inclusion, acceptance and safety?

A home and a play ground – during my time on nights, I saw the summer house provided a playground for the wild life of the hospital – foxes, rabbits, squirrels, wood pigeons and magpies proliferate as do the bats and may bugs. At one time a place for the feral cats too. Moths and all manner of insects – making it their home, their living room, their bedroom, their dining room, their bathroom and their playground.

A Community – they have formed throughout my 33 years a community meeting place, not just for people of the hospital but for the general community too. Dog walkers, wanderers and especially kids – another resting place, a chatting shop, a play ground, a teenage lovers lane, a drug den for sales and use of illicit substances, a pub for underage drinking and smoking.

A smoking shelter – with the implementation of smoking bans the summer house became an illicit smoking shelter – staff would congregate, smoke, chat, catch up on the gossip of their own and especially others lives, arrange nights out, disclose personal achievements and failures, seeking support and kindness.

A personal sanctuary – This is where through 33 years I’d sit and contemplate life, and from this make life decisions and consider how to handle situations that weren’t in my control – to begin with were my thoughts about psychiatry, personal issues of career plans, relationship plans and relationship ends, either of my making or those made by others. These summer houses know all my life secrets, and I trust that the details will never be shared. They were and still are my sanctuary, my friend and my confidante.

My last resting point after my very last 12 hour night shift at Whitchurch, was the summer house. I sat, lit a cigarette and reflected on 33 years – I saw myself and my colleagues and friends, through the decades – some no longer with us – but they were there with me for that final resting point. Also came to mind my family, friends and relationships – they were present with me too. I could see and hear them; they along with my memories above are my summer house, my special place.

Thank you to Tim Bennett

Guest blog post from Mark Doherty, Lead Nurse for Mental Health Services for Older People (MHSOP)

November 15th, 2016 by Admin No comments »Once, one of the “characters” died of old age, in his bed. His heart stopped. I heard the emergency call, and was told to rush up the stairs with the defibrillator, which in those days was the size of a fridge. The cables and paddles fell off and got tangled in my legs. When I finally got to the “chronic” ward it was, of course, too late. The ward staff were stricken with grief. “Good old_____” said one of the Nursing Assistants, “…he was a perfect patient, he was. He never shit the bed once.” You have to believe me when I tell you that the staff were genuinely upset by the death, and that the Nursing Assistant’s comment was meant as an expression of his admiration for the old guy. With such modest levels of acceptable behaviour, it is hardly surprising that we created a group of patients whose behaviour was totally unfit, and never would be fit, to survive in the outside world.

So we don’t do that anymore. In fact we hardly ever admit anybody at all, if we can help it; and even when we do it is for the shortest time possible, lest the toxins of the institution affect them. This is undoubtedly a good thing, and yet I worry, because I have a personal conviction that the outside world is as much a deforming institution as Whitchurch Hospital and its like ever was.

It is true that, as with many old institutions, Whitchurch was built on the outskirts of the city so that the unpalatable fact of mental illness could be kept at a distance and not cause offence. It is also true that the city then advanced to encompass the area of Coryton, and for most of the last hundred years the denizens of Whitchurch and Coryton have had to live with the redbrick spider and its green-domed water tower looming over them. It is fair to say that the local residents have coped quite well with this terrible burden. People who do not live in such circumstances are faintly discomfited by the idea—it must be like living next to a high security prison or a nuclear reactor: you are always waiting for the breach of protocol that leads to the escape of convict or radiation, or lunatic. But the locals in Whitchurch know the same thing that the locals in Cefn Coed or St. Cadocs also know: that the presence of an old psychiatric hospital in your village means precisely nothing; it is almost boring, because when the in-patients come out to shop or visit the pub or bank, it is a complete non-event. There is a disappointing lack of strangeness about those who have been diagnosed as mentally ill.

But people want it to be strange. Back in 1983 I had been out on the town one evening and had taken a taxi back to the Homes. Somewhere along North Rd., Drive said to me: “So you lives in Whitchurch ‘Ospital, then, is it?”

I replied in the affirmative. Drive narrowed his eyes a bit, gave this some thought, then asked his question: “Something I’ve always wondered about that place,” he said, “do you ‘ave much trouble with ’em howling in the night?”

I replied in the negative. He was clearly disappointed. He wanted, no doubt, tales of awesome lunacy, but I had none to tell.

Here is another memory from 1983. Every Saturday night, the Great Hall would be pulsing with pop music and chatter, and there would be a beery odour. Not a patients’ social function, not a staff reunion. The corridors would be full of drunken, unfamiliar people. Whitchurch Hospital was hired out on Saturday nights for wedding receptions; now, almost a quarter of a century on there must be at least some of those marriages surviving, with their memories of one humid and crapulent night in Whitchurch. It does seem an odd thing to do, and it hasn’t happened for some time, and yet only last week I was driving through the hospital’s main entrance and had to halt the car because of two young men in kilts posing with a bride and groom against a wedding car full of flowers and ribbons, a professional photographer snapping athletically away. How did people come to that decision? Where shall we have the reception, love? Where do you fancy for the photos? Castell Coch? Cathays Park? Cardiff Bay? I know, how about…

I suppose it just supports my contention that a psychiatric hospital is an ordinary place. Nothing, as Phillip Larkin said, like something, happens anywhere. And it’s as good a place as any to hold a wedding reception.

I moved out of Whitchurch for several years. Of course it wasn’t the same when I came back. It was falling to bits for one thing. Like the coal industry, it no longer has a place in somebody’s particular vision of the future, and so it has been neglected and is showing the terrible signs of that neglect.

As a Mental Health Professional whose teeth are getting quite long, I must applaud the closure of Whitchurch Hospital as a symbolic sweeping aside of the ancient asylum culture, clearing the way for a new build that will be fit for humans to inhabit. And I do applaud it. But it will be an ordinary building, the new one, a competent building; you and I know that it will possess not one hundredth of the aesthetic power and romance of Whitchurch Version 1.0. It will lack strangeness. Some of the old building is “listed”, and therefore parts of it will continue to exist to accommodate the flatlets or shopping centre or office facilities that are planned for the site, but it will be unrecognisable. It is difficult to see how the village of Whitchurch itself will retain its sense of character, unless the Water Tower is to remain.

I moved to Whitchurch Hospital to start my Registered Mental Nurse training when I was nineteen. A little room in the East Homes was pretty much my first experience of independent living.

But the nurse education went on in a building on the other side of the site, in a squat 1950s block. So my lessons were spent with a panoramic view of the hospital and the grounds. I started my training in February 1983. I was overwhelmed by two things: the little jars of real foetuses in the glass-fronted cabinet at the back of the classroom (I have never been able to work out what they had to do with psychiatry), and the view of the hospital with the trees in front of it. In February, the trees were bare and exhibited intricate branch-networks against a white sky, like the diagrams of bronchi, arteries and nerves I was being shown in anatomy lessons. At the age of nineteen, I thought I had been transported into the heart of a massive poem, and am still haunted by that time. If the new flats or offices find that they have a ghost, it may well be mine.

Thank you to Mark Doherty, follow Mark on twitter (@markdoherty1)

Exhibition at The National Museum, Cardiff

November 1st, 2016 by Admin No comments »We were invited to take part in the Re-Imagining Challenging History conference by Dr Jenny Kidd, lecturer at the Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural studies and Dr Rachelle Barlow, School of Music, Cardiff University.

Elen Phillips, Principal Curator Contemporary & Community History at St Fagans joned us with the amazing tablecloth made in 1917 at Whitchurch Hospital.

Huge thank you to everyone who made it a great experience including Alan Vaughan Hughes from Special Collections and Archives at Cardiff University, Eleri Evans from the Museum, Jenny Kidd, Rachelle Barlow, Elen Phillips and all those who shared their stories of Whitchurch Hospital with us.

Tea Party Photos

May 26th, 2016 by Admin No comments »Here are the photos that Craig Harper from Media Resources took on the 11th of March. Thank you to the Mental Health Clinical Board for permission to put on the website.

It was a lovely afternoon of meeting up with old friends and colleagues, thank you to all who came along.

Recognise anyone? Do get in touch if you were there or recognise some faces.